Normally, when people think of an architect they picture someone hunched over a drawing board, scribbling with a pencil.

Truth is, that’s not been the case for years. The computer entirely transformed every aspect of how architects work, from working through their first impressions to creating complex construction documents. But however impressive technology can get, there’s a lot to be said for continuing to work on paper.

One architect who believes sketching still has enormous value is Roberto Garcia. A Designer and Project Leader for Hames Sharley in Adelaide, South Australia, he sees hand-drawing as our most powerful means of conceptualising and representing architecture, one that can communicate complex notions in just a few evocative lines.

“Drawing by hand stimulates the imagination,” he says. “It helps to convey ideas, demonstrate functionality, visualise user flow, and illustrate anything that requires interaction. It is timeless.”

Indeed, a love of sketching was one of the key factors that led Roberto to architecture as a career in the first place. “I started very young,” he says, recalling how, as a ten-year-old in Peru, he would accompany his older brother to university and marvel at the possibilities of art and design. “By the time I was 12, I had my own drawing board, and I knew I wanted to be an architect.”

But it was after studying architecture and relocating to Australia that Roberto found his skills with pencil and paper had an additional benefit.

With only a poor grasp of English, he soon realised sketching was a way not only to showcase his ability as an artist but also to bridge the language gap.

“Sometimes, I have a complex thought in Spanish, and it does not always translate to English,” he says. Sketching, however, can act as a universal means to communicate. “When you draw, it’s the same. One of my professors used to say, ‘You know you are an architect if, instead of talking, you draw’.”

That ability to communicate simply but effectively has contributed to Roberto’s belief that hand-drawing is the most vital step in the design process – and with so much of the work of building design being done by computers, he is concerned that some architects are neglecting this crucial element.

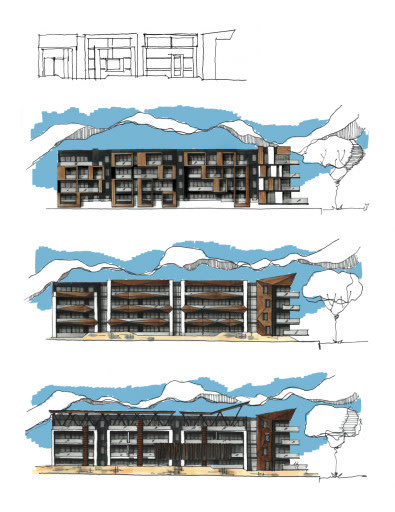

“Sketching is the step we all need to discover potential issues and solutions early on,” he explains. “A pen and a piece of paper are all you need to create ten different ideas from the same tracing paper.”Starting with a hand sketch and refining his concepts there means by the time Roberto is ready to start 3D modelling, he already knows exactly what he wants. “I’ll print, I’ll put another piece of tracing paper on top, and I’ll sketch over again until it is right,” he says. “There is a lot of back and forth between hand sketching and 3D modelling, but I think that is important.”

With sketching comes possibilities, and for many designers, it is an invaluable process of failure and refinement – it allows for fluid adaptation and the possibility that you can literally go back to the drawing board to get a design exactly right.

What’s more, a hand-drawn design speaks of an architect’s personality. “Presenting a render to a client, compared to a hand sketch, is simply not the same,” he says. With a hand sketch, clients not only have the chance to better appreciate the artistry of a design, they are also offered a deeper connection to it. Seeing the whole design lifecycle inevitably leads to clients being more engaged with the process: if software is efficient, pencil and paper are emotive.

“The more you get in touch with and develop your skills, the better you will be able to elaborate and design,” Roberto says, advocating hand-sketching as an essential skill for his team. “If ideas become more intricate, sketching can help those concepts evolve and shape architectural solutions.”